How to Develop Annotation Guidelines

This article describes where to start and how to proceed when developing annotation guidelines. It focuses on the scenario that you are creating new guidelines for a phenomenon or concept that has been described theoretically.

In a single sentence, the goal of annotation guidelines can be formulated as follows: given a theoretically described phenomenon or concept, describe it as generic as possible but as precise as necessary so that human annotators can annotate the concept or phenomenon in any text without running into problems or ambiguity issues.

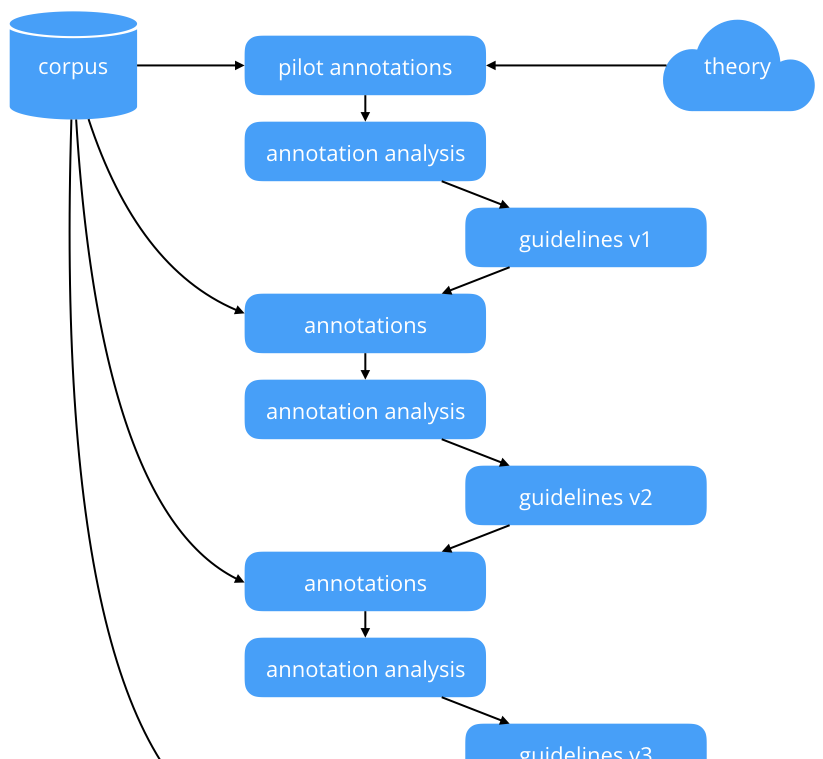

Developing annotation guidelines is an iterative process: Once a first version has been established, its shortcomings need to be identified and fixed, leading to a second version, which has shortcomings that need to be identified and fixed, etc. This process is displayed schematically in Figure 1. We will describe how to create a first version, and how to come from one version to the next. The most important idea is that in each round, the same text is annotated by multiple annotators independently. This is the main device that allows identifying these shortcomings.

Figure 1: General annotation workflow

Please note that in principle the entire workflow can be performed on paper or digitally. Digital annotation tools make it easier to compare annotations and force deciding on exact annotation boundaries (which words/characters are to be included). Paper-based annotations are more accessible and easier to set up, but make it (too) easy to skip over details. If you decide to make paper-based annotations, please pay attention to exact annotation boundaries.

Making Pilot Annotations

The first round of annotations is best done by annotators who are familiar with the theory that is to be annotated. As with the following annotation rounds, please annotate in parallel and discuss afterwards. It is not necessary to spend a lot of time on preparation. Specifying a list of references or theoretical works, or agreeing on a single text should be sufficient as a starting point.

Your time is spent best on discussing annotation disagreements. In particular in the very first round, many parameters are still undecided and likely to cause disagreement. At the beginning, you need to focus on the big questions:

- What is to be annotated? Every paragraph/sentence/word? Only paragraphs that fulfill a set of conditions?

- What exactly are the annotation categories? Are they related somehow? It sometimes helps to organize them in a hierarchy, as some categories subsume others (e.g., every finite verb is a verb).

- If you’re using a digital annotation tool: Make sure annotators have the possibility to attach comments to annotations. It helps a lot in the discussions later.

Annotation guidelines typically contain a lot of examples. So you best start collecting interesting/difficult/explanatory examples right away. Examples you find in real texts (possibly with some context) are usually advantageous over made-up ones.

Improving Guidelines

To improve guidelines in this manner, we first need to analyze annotations of the previous “round”, before we reformulate/refine the guidelines. This can be done by inspecting the annotation disagreements: These are cases in which different annotators made different decisions. These can be counted, of course, but it is more informative to talk about the disagreements with the annotators, and to let them explain their decisions.

Such an in-depth discussion with the annotators is fruitful in particular in the first rounds of the process. Once the annotators are trained and annotation guidelines are maturing, a quantitative view might be sufficient. For the latter, a number of metrics have been established (see Wikipedia: Inter-rater reliability for an overview; or Artstein, 2017). Analyzing the inter-annotator-agreement quantitatively gives you a number and allows measuring whether you are actually improving your annotation guidelines, but it does not distinguish different kinds of disagreement.

Some of the disagreements will be caused by annotators not paying attention, or by overlooking something – annotators are human beings after all. These can be fixed easily, without the need to refine the guidelines. It is good practice to let the annotators fix these mistakes by themselves.

Other kinds of disagreement can be expected to have impact on the guidelines: If two annotators made different decisions which are both covered by the annotation guidelines, it is likely that the annotation guidelines are contradictory in this aspect. The source of the contradiction should be identified and resolved.

Many disagreements will be caused when the annotators encounter cases that are not mentioned in the guidelines. In this case, either an existing annotation definition can be applied (perhaps with minor changes), or a new one needs to be defined. If a new definition is added, you need to think about the impact this definition has on the other definitions and annotations. Sometimes, this requires you to re-annotate what you have annotated before.

The actual discussions are likely to be lively and intensive, and tend to jump around between different aspects. It is not always easy, but it makes for better guidelines if this process is well structured and documented. Do not try to fix everything at once, but focus on one aspect at a time.

While going through this iterative process, two processes are likely to be intertwined: The annotation guidelines get better and the annotators get trained. Both are expected and, in principle, welcomed. But: In the end, the annotation guidelines are supposed to be self-contained and also applicable by untrained (or less trained) annotators. It is therefore important to pay attention not to develop rules within a project that are never written down. It will be much harder to integrate new annotators (even if someone drops out and has to be replaced) unwritten rules exist.

List of Annotation Guidelines

The following is a (not exhaustive) list of established annotation guidelines for various, mostly linguistic, phenomena. We provide this list as example for different kinds of tasks.

- Part of speech tagging in the Penn Treebank: The guidelines describe the tag set and its application, and have been developed in the Penn Treebank Project.

- TimeML: The TimeML guidelines describe the annotation of time expressions and related events in news texts.

- Coreference Resolution: Coreference resolution guidelines have been developed in the OntoNotes project. The goal here is to identify mentions in the text that refer to the same real-world entities.

References

Artstein, Ron. Inter-annotator Agreement. In: Ide Nancy & Pustejovsky James (eds.) Handbook of Linguistic Annotation. Springer, Dordrecht, 2017. DOI 10.1007/978-94-024-0881-2.